Lately, I’ve found myself in coincidental circumstances regarding the topic of counting calories. Specifically focused on the angle that counting calories is wrong because the numbers aren’t factual.

To be clear, I appreciate voices of reason and accuracy in the scientific community. When we quibble over details, it means a lot when considering phrases like “statistical significance.” I have no problem with attaining better methods, new approaches, or debunking old ones. People studying the research aren’t wrong to find flaws in exact calorie counting. Doing your job well and reporting on inaccuracies isn’t the issue. Discouraging the average dieter who is trying to change their life while attacking everything they’ve been doing, well…

The problem occurs when inaccuracies are overblown for clickbait or selling a different (and always equally as flawed/statistically sketchy) method. Again the pattern emerges (as it does quite frequently in the health industry) that your effort is useless or even part of a compulsive disorder but that you should “look at our method over here.” The calorie as we know it is dead, useless; and if you take part in counting those numbers, you’re doing it wrong or so they say.

Spoiler 1: The average assessment of caloric content is erroneous.

Spoiler 2: Being obsessive about the numbers isn’t the answer to your body composition problems in the first place.

Spoiler 3: There are 101 ways and plans to change your diet that have nothing to do with the knowledge of calories; however, this in no ways means it’s meaningless or destructive knowledge to obtain.

What Does the Research Say about Caloric Accuracy?

How accurate are the general calories we know of today? How close do those nutritional facts line up?

According to some research (here, here, and here) and depending on the food (mostly nuts), they line up pretty closely or are only sort of “off” which leaves you with—not that bad.

It’s “not that bad” when to trying to exhume energy in a measured “vacuum” to mimic the effects of caloric burn in the human body. When you think of it like that, it’s downright magical.

When you think of it as needing to measure, with almost total and complete accuracy within a tenth or centimeter—in order to say, deliver a calculated drone strike and avoid civilian casualties—no no, I wouldn’t use this method of measure.

There are also factors including digestion or cooking which can affect caloric numbers. Often, it’s as simple as bringing the fat out. In studies, we see that unless the fat is heated enough or ground, there can be leftover whole particles in stool. The “shell” acts as a shield to break down the fatty acid composition. If you’re a lazy chewer, it’s even fewer calories absorbed. Heating nuts, for example, can increase the calories absorbed. In short, you get more calories with a nut butter than the raw nut. Let me stop you now if you think it’s a good idea to be inefficient when chewing your food; you want to absorb your food.

We see similar things in heating with fat in steaks. A rare steak will release fewer calories than one that is well-done. Foods react to enzymes, heat, and individual digestive systems in different ways.

It should be noted that a lot of the time calories are less than we assume, not more. But most articles leave that part out in order to entice you to buy something. Nothing wrong with selling but should you scare first? I don’t think so.

If you look at independent companies and their nutritional facts, it’s a lottery at best. A lawsuit was recently filed against the Lenny & Larry’s Cookie Company for misrepresenting their nutritional facts.

The FDA allows variations in error levels and rounding of caloric and macronutrient content. It should be noted this can change on a yearly basis and new rules have recently been released for the nutrition labels themselves.

Take home?

We have a solid idea of the caloric content in our food but it isn’t precise. That doesn’t mean the numbers, even in ranges, are worthless to know. They aren’t so dramatically wrong that they are useless; you can work with them if you use a system.

Should You Worry about the Count of Calories?

As I stated, accurate caloric knowledge should never be touted as the answer. Trying to understand precise caloric intake in a free-living society is akin to learning how to juggle for the first time with eggs.

But caloric content is not meaningless knowledge. It’s a skill and tool you can use.

If someone has a good grasp on portion intake, is routine, and doesn’t have a tendency to severely overeat or binge, I will likely never talk to them about calories. Instead, I will educate them and forge a food strategy. I will explain how they can make small shifts in their routine to land in the zone they need, be it fat loss, maintenance, or muscle gain.

But if someone has a poor grasp on portion intake, an erratic food schedule, and a tendency to overeat and binge, then we will talk about calories. I will educate them on understanding their intake need in a more detailed manner. This does not mean they have to spend their life counting calories (or at all), but it does mean they will get a hard lesson on generalized calorie counts released by research facilities. They will learn the zones and ranges of calories in products, how calories relate to them, and how much (roughly) they may burn in a day.

It is a skill you can learn, if you think critically and with logic.

Hone the Skill Instead of Worrying Over the Numbers

I don’t care who you are, you’ve improved at a skill. Driving? Athletics? Cooking? Child rearing? Reading? Every person has improved at something. To get visual, let’s do an exercise.

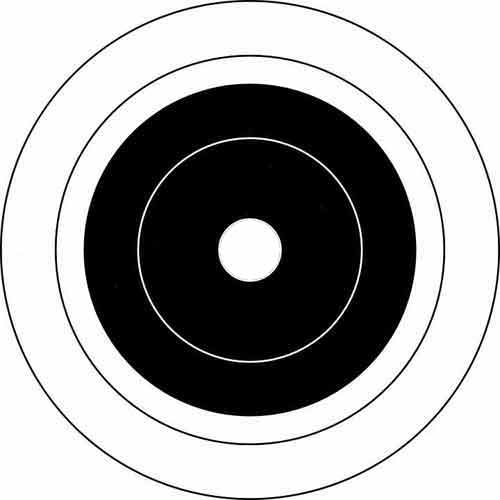

Below you will find a picture of a set of circles.

1. Take your mouse pointer or touch pad to the furthest right edge of your computer or laptop.

2. As quickly (but as controlled) as possible and in one swipe, guide the pointer to the circles attempting to land as close as you can to the middle circle.

3. Repeat your attempts until you feel you’ve honed your speed and achieved a relative “mastery” of this exercise.

4. Don’t feel bad if you can’t land in the middle. That’s not the point.

Disclaimer: I am not responsible for anyone breaking into a blind rage and busting their computer, mouse, keyboard, or any other object because of frustration due to this exercise. `

What you learn from this is over time your exaggerations and misses decrease. Ideally, you nibble away until you land in your target. For some, you may nail it on your first venture. For others, you may never achieve perfection but you do get closer.

Caloric measuring is the very exercise you practiced above. You take a little food out here, add a little there, and then manipulate it based on your goals. But unlike the immediate feedback from the circles above, determining if one has landed on the “target” can be a tiring exercise.

“Did I gain muscle? Am I retaining water? Have I given it enough time? Did I have too much sodium? Carbohydrate intake? Am I dehydrated? Am I too hydrated?”

Unless the deficit is extreme, change is subtle.

Summary

The point of this article is to drive home the main mission statement that caloric accuracy is not the goal, learning your caloric need is.

It doesn’t matter if 2,000 calories is actually 1,800 calories or 2,200 calories (in testing reality) as long as you adjust for your needs correctly. You shouldn’t be shooting for an arbitrary number, not in weight, activity, etc. Rarely, unless in competition, does the scale matter. History shows us that 155 pounds can look very different on people of the same heights depending on muscle and fat mass.

It’s not about the accuracy of the numbers.

(Extra: I’ll be releasing a (free) review on the subject soon. I’ll also be presenting on the topic: Variations and Determining Factors in Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE): A Lesson for a Better Understanding of Daily Metabolic Rate at the GGS weekend this April. Got your ticket?)

To Summarize:

1) Caloric stats vary in accuracy. These variations are still being tested.

2) Everything from heat, health, and the truthfulness of companies determine the accuracy of calorie counts.

3) We have a solid general idea of caloric content in food—it just isn’t precise.

4) Perfection over intake amount isn’t the goal and can lead to obsessive and unrealistic expectations.

5) Caloric knowledge is one of many methods and tools; counting calories is not the only tool in the box.

6) Focus on honing your intake skills and learning how many “calories” your body needs instead of worrying about the numbers.

—

References: